Can a President That Is Impeached Run Again

The Causes for Which a President Can Exist Impeached

"What, so, is the meaning of 'loftier crimes and misdemeanors,' for which a President may be removed? Neither the Constitution nor the statutes have determined."

The Constitution provides, in express terms, that the President, also every bit the Vice-President and all civil officers, may be impeached for "treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors." It was framed past men who had learned to their sorrow the falsity of the English maxim, that "the male monarch tin can do no wrong," and established past the people, who meant to hold all their public servants, the highest and the lowest, to the strictest accountability. All were jealous of whatever "squinting towards monarchy," and determined to allow to the master magistrate no sort of purple amnesty, but to secure his faithfulness and their own rights by belongings him personally accountable for his misconduct, and to protect the government past making acceptable provision for his removal. Moreover, they did not mean that the door should not be locked till after the equus caballus had been stolen.

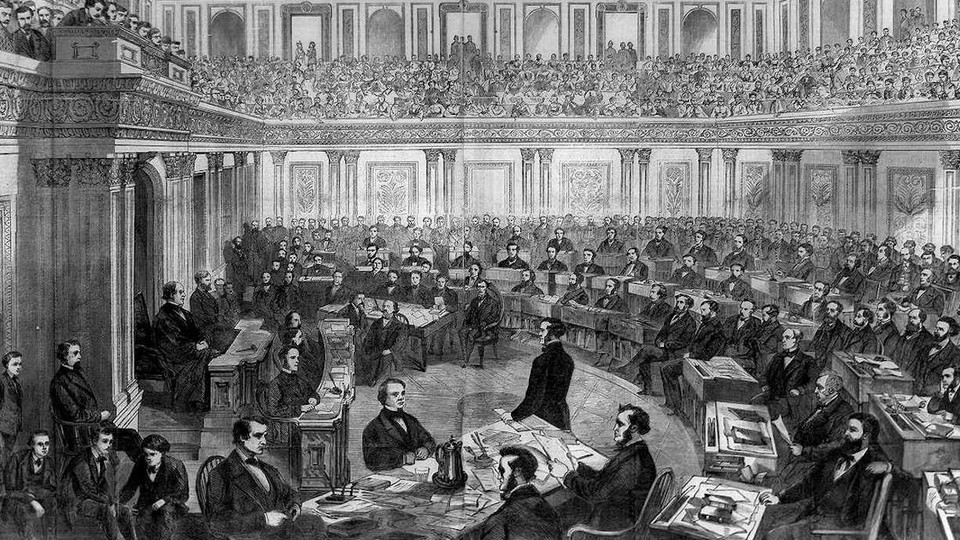

Past the Constitution, the House of Representatives has "the sole ability of impeachment," and the Senate "the sole power to try all impeachments." When the President of the U.s. is tried on impeachment, the Main Justice is to preside. The concurrence of two thirds of the members present is necessary to captive. "The President, Vice-President, and all ceremonious officers of the Us, shall exist removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors." Only judgment cannot "extend further than to removal and disqualification to agree and enjoy and office of honor, trust, or profit nether the United States." Thus it is obvious that the founders of the authorities meant to secure it effectually against all official corruption and incorrect, by providing for procedure to exist initiated at the will of the popular branch, and furnishing an easy, rubber, and sure method for the removal of all unworthy and unfaithful servants.

Past defining treason exactly, by prescribing the precise proofs, and limiting the penalty of it, they guarded the people against one grade of tyrannical corruption of power; and they intended to secure them effectually confronting all injury from abuses of another sort, by holding the President responsible for his "misdemeanors," — using the broadest term. They guarded advisedly confronting all danger of pop excesses, and whatsoever injustice to the accused, by withholding the general power of punishment. This term "misdemeanor," therefore, should exist liberally construed, for the same reason that treason should non be extended by construction. It is non better for the state that traitors should remain in function than that innocent men should be expelled. Besides, information technology is true in relation to this process, that the higher the post the higher the crime.

What, then, is the meaning of "loftier crimes and misdemeanors," for which a President may be removed? Neither the Constitution nor the statutes have determined. It follows, therefore, that the House must judge for what offences it volition present articles, and the Senate decide for what it volition convict. And from the very nature of the wrongs for which impeachment is the sole adequate remedy, as well equally from the fact that the office of President and all its duties and relations are new, it is essential that they should be undefined; otherwise there could exist no security for the land.

But information technology does not by whatsoever means follow that therefore either the House or the Senate tin deed arbitrarily, or that there are not rules for the guidance of their comport. The terms "loftier crimes and misdemeanors," like many other terms and phrases used in the Constitution, as, for instance, "pardon," "habeas corpus," "ex post facto," and the term "impeachment" itself, had a settled meaning at the time of the establishment of the Constitution. There was no need of definition, for it was left to the House as exhibitors, and the Main Justice and the Senate every bit judges of the articles, to apply well-understood terms, mutatis mutandis, to new circumstances, every bit the exigencies of state, and the ends for which the Constitution was established, should require. The bailiwick-matter was new; the President was a new officeholder of land; his duties, his relations to the various branches of authorities and to the people, his powers, his adjuration, functions, duties, responsibilities, were all new. In some respects, one-time customs and laws were a guide. In others, at that place was neither precedent nor analogy. But the mutual-law principle was to be applied to the new matters according to their exigency, as the mutual law of contracts and of carriers is practical to wagon past steamboats and railroads, to corporations and expresses, which have come up into existence centuries since the law was established.

Impeachment, "the presentment of the most solemn grand inquest of the whole kingdom" had been in utilise from the earliest days of the English Constitution and government.

The terms "loftier crimes and misdemeanors," in their natural sense, comprehend a very large field of actions. They are broad enough to cover all criminal misconduct of the President, — all acts of commission or omission forbidden by the Constitution and the laws. To the discussion "misdemeanor," indeed, is naturally fastened a yet broader signification, which would embrace personal character and beliefs as well as the proprieties of official bear. Nor was, nor is, there any just reason why it should be restricted in this direction; for, in establishing a permanent national government, to insure purity and dignity, to secure the confidence of its ain people and command the respect of strange powers, it is not unfit that civil officers, and most especially the highest of all, the head of the people, should exist answerable for personal demeanor.

The term "misdemeanor" was likewise used to designate all legal offences lower than felonies, — all the small-scale transgressions, all public wrongs, not felonious in character. The common law punished whatever acts were productive of disturbance to the public peace, or tended to incite to the committee of criminal offense, or to hurt the health or morals of the people, — such as profanity, drunkenness, challenging to fight, soliciting to the committee of crime, carrying infection through the streets, — an endless variety of offences.

These terms, when used to draw political offences, have a signification coextensive with, or rather analogous to, but yet more extensive than their legal acceptation; for, equally John Quincy Adams said, "the Legislature was vested with power of impeaching and removing for trivial transgressions beneath the cognizance of the law." The sense in which they are used in the Constitution is rendered clearer and more precise past the long line of precedents of decided cases to be found in the State Trials and historical collections. Selden, in his "Judicature of Parliament," and Coke, in his "Institutes," refer to many of these, and Comyns names more than than fifty impeachable offences. Amid these are, subverting the fundamental laws and introducing capricious power; for an ambassador to requite false information to the rex; to brand a treaty between 2 foreign powers without the knowledge of the king; to deliver up towns without consent of his colleagues; to incite the king to human action against the advice of Parliament; to give the king evil counsel; for the Speaker of the House of Commons to refuse to proceed; for the Lord Chancellor to threaten the other judges to make them subscribe to his opinions.

Wooddeson, who began to lecture in 1777, and whose works express the sense in which the terms were understood by the contemporaries of the founders of the Constitution, says that "such kinds of misdeeds as peculiarly hurt the commonwealth past the abuses of loftier offices of trust are the most proper, and have been the well-nigh usual grounds for this kind of prosecution"; — "as, for example, for the Lord Chancellor to human activity grossly opposite to the duty of his role; for the judges to mislead the sovereign by unconstitutional opinions; for any other magistrates to attempt to subvert the fundamental laws, or introduce arbitrary power, equally for a Privy-Councillor to propose or support pernicious or dishonorable practices."

These text-writers seem to accept been referred to and followed by our later ones.

But to the offences enumerated by these authorities we must add together others taken from cases in the Land Trials. The High Court of Impeachment had included amongst political high crimes and misdemeanors the following, viz.: for a Secretary of Land to corruption the pardoning power; for the Lord Chancellor and Principal Justice of Ireland to attempt to subvert the laws and government and the rights of Parliament; for the Attorney-General to adopt charges of treason falsely; for a Privy-Councillor to try to alienate the affections of the people; for the Lord Chancellor to assume to manipulate with the statutes, and to command them. It had been held to be a misdemeanor to incite the king to sick-manners; to put abroad from the king practiced officers, and put about him wicked ones of their own political party; to maintain robbers and murderers, causing the king to pardon them; to get ascendency over the king, and turn his heart from the peers of the realm; to prevent the great men of the realm from advising with the king, relieve in presence of the defendant; and to cause the king to appoint sheriffs named by them, so as to go such men returned to Parliament as they desired, to the undoing of the loyal lords and the good laws and customs; to taunt the king'southward councilors, and phone call them unworthy to sit in council when they advised the king to reform the government; or to write messages declaring them traitors.

The nature of the charges may be illustrated past one of the allegations against an evil judge. We requite Article 8.: "The said William Scroggs, being advanced to exist Lord Chief Justice of the Court of King'due south Bench, ought, by a sober, grave, and virtuous conversation, to have given a good example to the rex'south liege people, and to demean himself answerable to the dignity of then eminent a station; withal on the contrary thereof, he doth, past his frequent and notorious excesses and debaucheries, and his profane and atheistical discourses, affront Omnipotent God, dishonor his Majesty, give countenance and encouragement to all manner of vice and wickedness, and bring the highest scandal on the public justice of the kingdom."

Such was the nature of political offences, as known to the framers of the Constitution. It answered to the natural sense of the terms of the Constitution, as understood by the people in establishing it. And it is plain that the founders of the regime meant to establish, what in such a authorities is vital to the safety and stability of the state, a jurisdiction coextensive with the influence of the officers subjected to it, and with their official duties, their functions, and their public relations.

The Federalist, in treating of this jurisdiction of the Senate, regarded it as extending over "those offences which go on from the misconduct of public men" and termed "political, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to social club itself."

The people of America meant to balance their authorities on executive responsibility, and to apply to the President the principles which had been established as applicative only to the ministers, servants, and advisers of the king. Just to show what they regarded as the range of majestic duty, they had put on tape a list of charges against their own male monarch himself, commencing thus: "He has refused his assent to laws the most wholesome and necessary for the public expert," — on which they justified revolution. The Declaration of Independence will help in determining what they would regard every bit offences of the Executive.

No President has been impeached. Simply the charges exhibited against several other public officers throw low-cal upon this subject. In 1797, manufactures of impeachment were found against William Blount, a Senator. The misdemeanors were not charged as being done in the execution of any office under the United States. He was non charged with misconduct in role, only with an attempt to influence a U.s.a. Indian interpreter, and to amerce the affection and conviction of the Indians. After the impeachment was known, but before it was presented to the Senate, the Senate expelled him, resolving "that he was guilty of a high misdemeanor entirely inconsistent with his public trust and duty as a Senator."

In 1804, John Pickering, Guess of the Commune Courtroom of New Hampshire, was removed for, — 1. Misbehavior every bit a judge; and amongst other causes, 4. For actualization drunk, and frequently, in a profane and indecent way, invoking the name of the Supreme Beingness.

In 1804, Approximate Chase was impeached and tried for capricious, oppressive, and unjust carry, in delivering his opinion on the constabulary beforehand, and debarring counsel from arguing the police force; and for unjust, impartial, and intemperate deport in obliging counsel to reduce their statements to writing, the use of rude and cynical language, and intemperate and vexatious behave.

These are cases of contemporaneous exposition. There have been other cases in the various States, and some more recent ones in Congress; simply they are not necessary to illustrate the subject. Just on the eve of the war, the Senate expelled Bright for writing a alphabetic character to Jefferson Davis, introducing a human being with an improvement in burn down-arms as a reliable person.

Equally Judge Story remarked, "Political offences are of so various and complex a graphic symbol, so utterly incapable of being defined or classified, that the task of positive legislation would exist impracticable, if it were non almost cool to endeavour information technology." Referring to the text-writers we have named, and the causes of impeachment enumerated by them, he seems to justify the extremest cases by saying that, though they now seem harsh and severe, "peradventure they were rendered necessary past existing corruptions and the importance of suppressing a spirit of favoritism and court intrigue." "Just others once again," he adds, "were founded in the well-nigh salutary public justice, such as impeachments for malversations and neglects in office, for official oppression, extortion, and deceit, and especially for putting skillful magistrates out of office and advancing bad." He puts a case, on which he expresses no opinion, in such form that there can scarcely be any doubt of his stance, or any possibility of two opinions apropos information technology. "Suppose a judge should countenance or aid insurgents in a meditated conspiracy or insurrection a meditated conspiracy or insurrection against the authorities. This is not a judicial act; and yet it ought certainly to be impeachable."

Thus it appears that the political offences of the Constitution for which civil officers are removable embrace, too the high crimes and misdemeanors of the criminal law, a range as wide as the circle of official duties and the influences of official position; they include, non only breaches of duty, but also misconduct during the tenure of office; they extend to acts for which there is no criminal responsibility whatsoever; they reach even personal deport; they include, non merely acts of usurpation, but all such acts every bit tend to subvert the just influence of official position, to dethrone the office, to contaminate lodge, to impair the government, to destroy the proper relations of civil officers to the people and to the government, and to the other branches of the authorities.

In fine, it may almost be said, that for a President to accept washed anything which he ought not to accept done, or to have left undone anything which he ought to have done, is just cause for his impeachment, if the Firm by a majority vote feels chosen on to make information technology the ground of charges, and the Senate by a two-thirds vote determines information technology to exist sufficient; for the safety of the country is the supreme law, and these bodies are the final judges thereof.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1867/01/the-causes-for-which-a-president-can-be-impeached/548144/

0 Response to "Can a President That Is Impeached Run Again"

ارسال یک نظر